Site Navigation: Home » Oakland_Nature_Center

Brighton C Cain – Oakland Naturalist and Oakland’s unofficial “Man-at-the-lake”. Excerpts from “A Man Who Molded Generations” by Paul Covel:

It happened on the campus of Mills College in Oakland one beautiful spring morning. The quarry had been pinned down in a patch of shrubbery. The eager pursuers were about to surround its hideout when the tall young man in khaki, with binoculars held at the ready, gave the command to freeze. Six scouts, also armed with binoculars, came to a dead halt and stopped their excited chatter. From their leader came a strange series of squeaks, chirps, and tut-tut-tut-tuts in rapid succession. A pause and similar sounds came from behind the shrubbery. This performance was repeated several times. Finger to lips, the leader gathered his scouts around him. “I think it may be a yellow- breasted chat, a rare transient hereabouts,” he confided sotto voce.” Chats behave like that. Let’s spread out around it quietly maybe we can catch sight of the fellow.” The challenging sounds continued. Scouts and an adult male guest on the hike silently crept around the thicket. There crouched the quarry —two lovely Mills girls, both with binoculars and one with an Audubon bird caller in hand. Standing aghast were six disappointed boy birders, a much embarrassed leader and a rather pleased guest birder. Who was this leader whose fame in identifying and talking back to the birds was legendary, but who won many more laurel for his accomplishments with Boy Scouts? It was Brighton C. Cain.

In 1924, 26 year old Stanford trained entomologist Brighton C. Cain (also known as “Bugs” and BC Cain) started working for the Oakland Area Council, Boy Scouts of America as their Naturalist. The mecca of Boy Scouts in Oakland was the location of Camp Dimond in the Oakland hills (present day Montera Middle School). Alluring trails led off through nearby Joaquin Miller Park and through the Skyline Redwoods into the urban wilderness of the new East Bay Regional Parks. But the first goal of most of the scouts who hiked up to Dimond Camp was the Bug House, the small unpretentious structure was turned over to Bugs Cain. Signs reminded them to approach quietly; birds were being fed and caught for banding in the rear of the place. Deer, skunks, and raccoon might be seen in early morning or toward evening around Dimond Camp, though Bugs didn’t welcome them to his bird feeding and banding station.

The house of wonders, the Bug House, combined elements of museum, mini -zoo, classroom, planetarium, and window lookout on the feeding station. No boy ever emerged the same as when he entered. Even the occasional sophisticated father who dutifully brought his scout would be caught in the contagion of excited boys and emerge a somewhat better man.

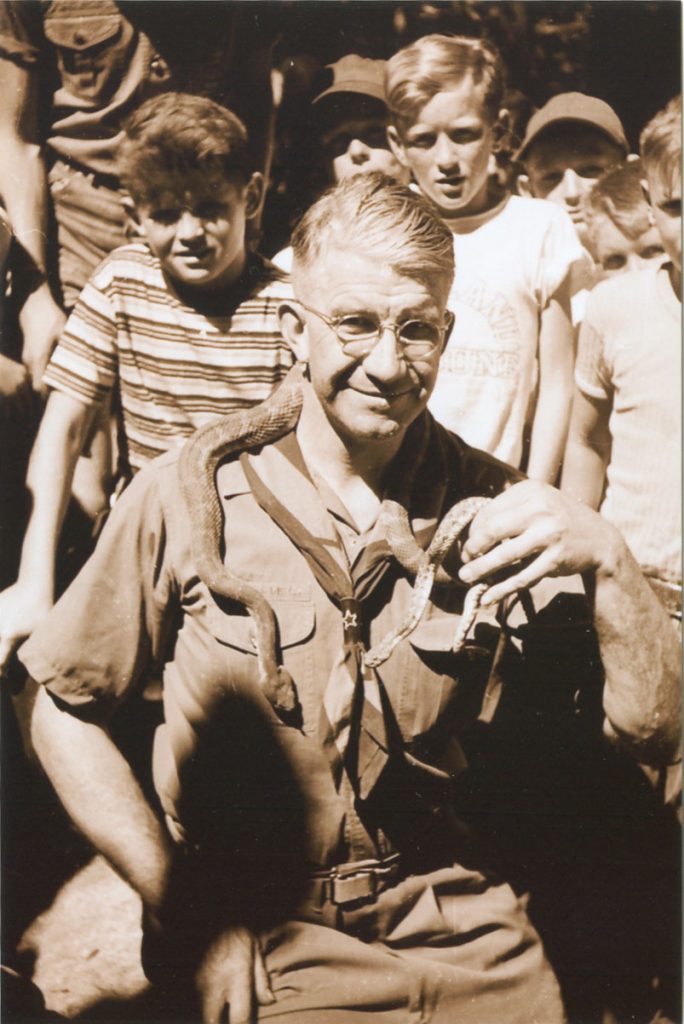

Most exciting of all exhibits to the visitor were the snakes. They lived mostly comfortable existences in captivity, sharing meals of mice, frogs, or lizards, according to each species’ tastes. Only the rattlesnake cage bore a padlock. But that didn’t mean they were untouchable. BC Cain regularly brought them forth, demonstrated their amiability, even took them along on his presentations. He was able to prove a little-known scientific fact, later confirmed by the renowned Dr. Raymond Ditmars, that a rattler can stand only about twenty minutes of direct sunlight on its head before fatal consequences ensue.

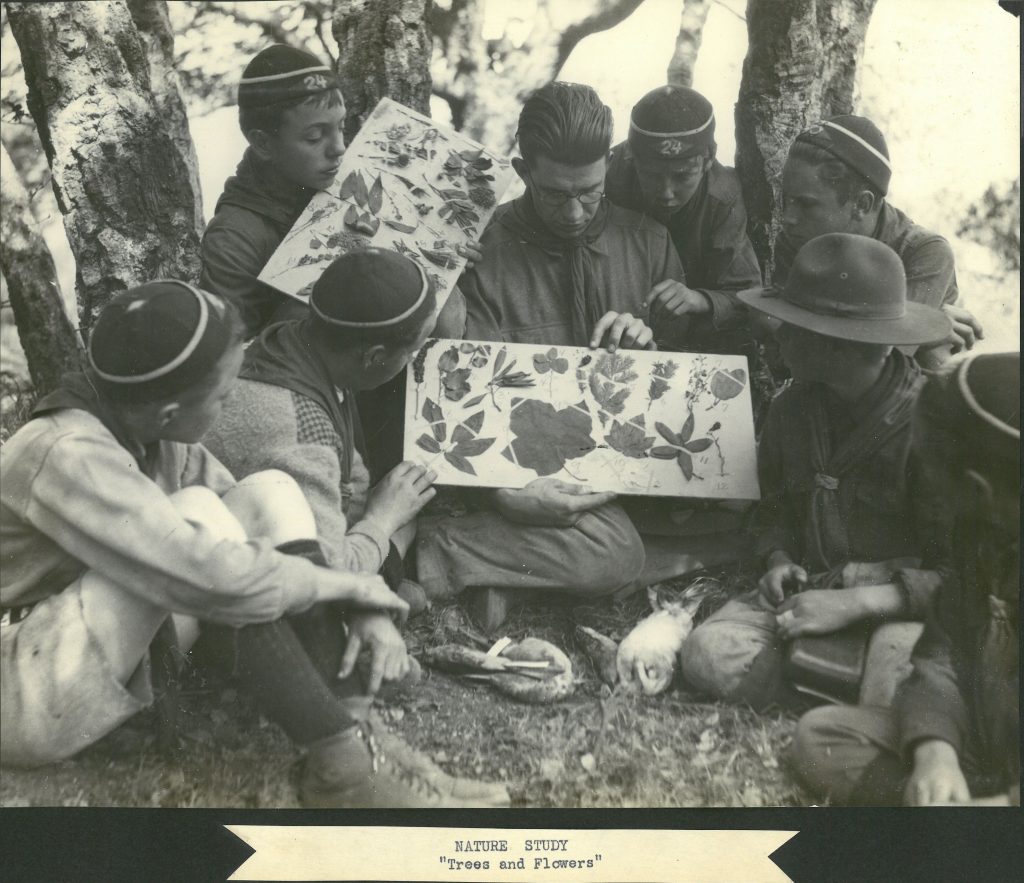

Merit badges for advancement were numerous and tough in those earlier years of Scouting. One of Bugs Cain’s principal tasks was to prepare and to pass applicants for a formidable array of badges in the natural sciences and outdoor skills. Among these the Bird Study merit badge seemed to be the toughest and even the most dreaded by many scouts. Whenever the name of Bugs comes up in the reminiscences of some successful business and professional men, they still recall their struggles to pass the Bird Study merit badge. Birding with Bugs Cain was not just a matter of learning to identify a required number of species, their songs and calls. That was just the beginning. Before the eager Scouts could board the venerable Scout bus for the birding location, there was the “ritual of the binoculars.” This precious loaned collection had been gathered from generous dealers and other friends of scouting.

Like the tough drill sergeant presenting the rookie with his first rifle, Bugs would carefully clean each lens and explain the focusing controls as he handed them out to the neophyte birders. Once in the field it wasn’t enough for Bugs’ students just to decide the proper name for the bird in the glass. Why was the bird in that particular kind of tree or bush? What sort of insect, seed, or fruit was it seeking? How was it using its bill or feet to secure the food? So each boy received a mini- lesson in ecology, even if there wasn’t a merit badge for that subject at that time. Back at the Bug House, their heads buzzing with impressions of sightings and confusing voices, the bird badge seekers were not finished for the day. Bugs would seat them and bring out his collection of shoe boxes full of study skins of birds. Then would begin a “tools of the trade” recognition quiz. Covering most of the bird’s body with his hands, he would expose a bill or foot for identification. Scouts who had looked and listened attentively during the field trip would pick out the swollen bill of a grosbeak, the long scratching claws of a towhee, or the flat, broad, bug -scoop bill of a flycatcher or swallow. All this they had better remember when final tests came!

Bugs was particularly proud of a handful of young high school birders who had organized the Oakland Ornithological Club. These dedicated youths had prepared and published a first-ever publicly available List of the Birds of Lake Merritt and Lakeside Park. Cain spent much time with this club and other scouts at Lakeside and other urban parks. He was enthusiastic about the parks’ wealth of plant materials and wanted identification lists prepared. Conspicuous in his scout uniform and broad-brimmed hat, he became a genial question answer man for the curious public. At other times he assumed the warden role when he caught boys with air rifles or starting fires in the hill parks. Finally the superintendent of parks and the park commissioners recognized this man’s value. He was summoned to a commission meeting and handed a metal badge bearing the words: “Naturalist, Oakland Park Department.” No salary accompanied this exalted title, but Bugs was immensely pleased. And what became of the very special group of Bugs’ followers, the Oakland Ornithological Club? Such juvenile organizations are generally not long lived; the demands of higher education scatter and preoccupy them, followed by romances, careers, and marriage. Indeed, such a succession of events befell most of these young bird watchers. They became professors, farmers, government workers, naturalists, and businessmen. But the magic of Bugs’ enthusiasm and leadership stayed with them. Even to the time of this writing they hold regular annual get together in some natural environment and recall those rich adventures in hills and canyons, at shorelines and marshes around San Francisco Bay. A special event staged by naturalist Cain during summer or early fall was the Indian Foods Cookout. Teaching survival skills which might someday prove useful to Boy Scouts on wilderness treks was one objective.

In 1944 the loan for the Dimond property had been paid off, however in 1948 came a mortal blow at the height of Cain’s popularity and achievement. The Oakland Area Council of the Boy Scouts was forced to sell the Camp Dimond property to the Oakland School department for two new schools. A chorus of protests arose from scouts and scout leaders of all ranks, but the council did not have the funds nor the power to reverse the decision.

The Oakland Public Schools required space for two new schools and the site of Camp Dimond was required. Through condemnation the school district would officially take possession of the property in May of 1949. Although Dimond was still actively being used, expensive sewer upgrades were required and Housing tracts were crowding in around the camp’s perimeter. The Council would be better off taking the proceeds for Camp Dimond to enhance its wilderness camp in the Livermore hills.

Camp Dimond was sold and some of the funds were used construct buildings at Rancho Los Mochos in the Livermore hills. The contents of the Camp Dimond Bug House were moved to the new Bug House at Camp Meek in San Lorenzo (across from present day San Lorenzo High school) a small weekend camp. No longer could the local Scouts hike or take a bus from their homes to camp whenever they felt like it. Cain was no longer needed as a nature counselor except during weekend and vacation campouts at Rancho Los Mochos or at the more distant Dimond-0 in the Sierra’s.

There was plenty of work to do in the routine scout organization and paper shuffling. Bugs tried this life of a regular scout executive, reporting to the new downtown offices. However, his heart wasn’t in it, and he retired with the Boy Scouts of America after twenty-six years of distinguished service in September of 1950. He tried a job as a student counselor at the Menlo School for a short time but he couldn’t seem to find another niche. Sadly, Bugs took his own life and died alone in his car in May of 1951.

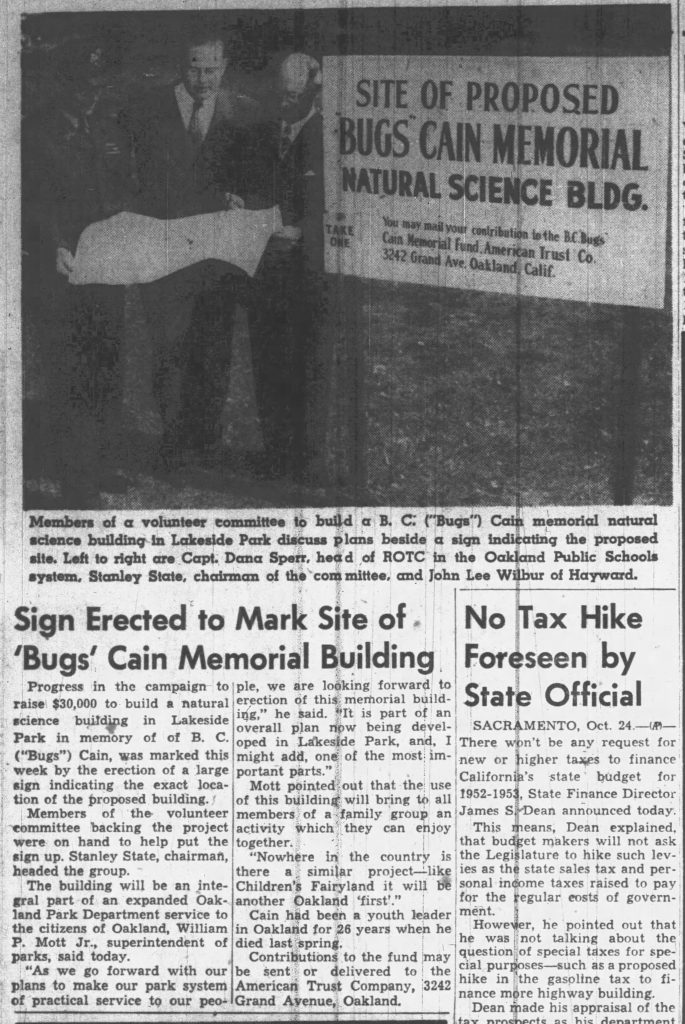

The youth and Scouts of the Eastbay lost a gifted teacher, interpreter and naturalist. This man must not be forgotten, was the reaction of a generation of scouters, grateful parents, and various associates of Cain. Oakland Parks Superintendent, William Penn Mott, Jr., who had managed to establish a full-time park naturalist program in 1947, came up with the right answer. Build a Nature Science Center close to the popular duck feeding area in Lakeside Park and name it for Brighton Cain. Contributions poured in from many quarters. The well-known bird photographer Laurel Reynolds gave a benefit film showing, and Harry C. Adamson, a noted waterfowl artist whose early drawings had won Bugs’ praise, donated a painting as a door prize.

Starting in August 1951, a campaign was put together to raise $30,000 for the BC Cain Natural Science Building at Lakeside Park. Governor Earl Warren whose two sons were in Oakland Scouts expressed his support by saying “Bugs was one of Oakland’s finest citizens, the inspiration which he gave to the Boy Scouts of the Oakland Area, including my own boys is beyond measure”. When the committee was still a few thousand dollars short of its goal, Bill Mott enlisted the aid of the Oakland Rotary Club and finally extracted $10,000 from the Oakland City Council to reach the goal.

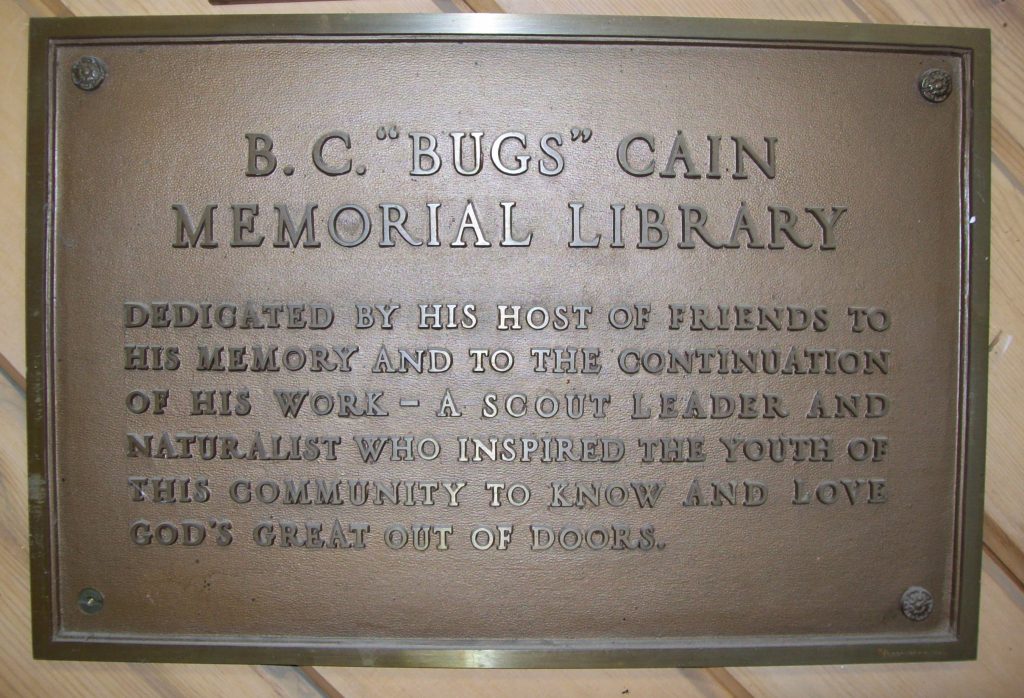

In 1953 the center was constructed and renamed the Rotary Natural Science Center. The doors to the new building were opened and the BC Cain Memorial Library containing many of Cain’s books and specimens from the Camp Dimond Bug House were available for all to see. Since 1953, many Scouts still benefit from the treasures of the Bug House located at the Nature center to prepare for their merit badge examination and to honor Brighton C. Cain, Oakland Area Council, Boy Scouts of America and Lake Merritt Naturalist.

Oakland Nature Center

Interior of Nature Center

Interior of Nature Center

Dimond-O, 1944, Rattlesnake

Portrait of Cain in Oakland Nature Center Libary

Dimond-O, 1944 – BC Cain teaching Scoutcraft

Dimond, 1923 – BC Cain, Bird Study

Camp Dimond Leaders – Cain on Right

STEM

Order of the Arrow